The conventional wisdom around industrial policy since the 1980s has been that the best bet is for states to keep a hands-off approach and let the market regulate itself. This is changing, with important implications for GCC countries, many of which have industrial growth at the heart of their economic development agendas.

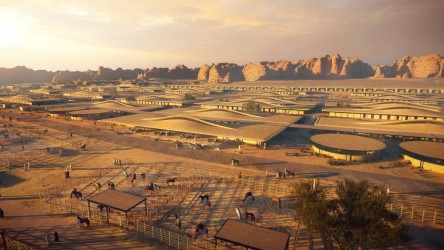

For example, Saudi Arabia’s industrial sector contributed $88.26bn to its GDP in 2020; the country aims to boost that to $377.06bn by 2035.

Meanwhile, the UAE has launched its “Operation 300 Bn” industrial strategy, which seeks to increase GDP contribution from $36.2bn to $81.7bn by 2031.

Finally, Abu Dhabi recently announced an investment of $2.7bn with a goal of more than doubling the size of its manufacturing sector to $46.8bn.

State impetus

What has triggered this amplification of state involvement when it comes to industrial policy?

A confluence of global events in recent years—including the pandemic and geopolitical shifts—has powered a resurgence of increased governmental involvement in the form of subsidies, trade protection, regulation, credit provision, direct investment, and access to markets and technology across the globe.

The Inflation Reduction Act and the CHIPS and Science Act in the US are two prominent examples, as is the European Green Deal. Implemented well, state involvement can likewise unlock considerable value for GCC nations through state-led industrial diversification. The key is taking a balanced approach—and therein also lies the greatest challenge.

Governments can help investors overcome market and coordination failures, nudge them into higher-tech sectors, and facilitate experimentation with new products and processes. In the best cases, like the East Asian industrialisers, the state can be midwife to whole new globally competitive industries.

And yet, for all the good that state involvement can bring, it also has the potential to undermine progress, stifle competition, and contribute to industrial failure. These failures can happen quickly; however, history shows they are more often akin to a slow death by a thousand cuts. Leaders in industry and government can benefit from the lessons of history to understand what has worked and what hasn’t.

Choosing outcomes

A country’s level of development is an important determinant when it comes to how much it can benefit from state involvement.

Advanced, diversified economies with access to the latest technologies have the advantage of a muscular private sector and less to gain from government involvement with industrial policy.

For countries with developing economies still in the nascent stages of building that muscle, state involvement can offer a stable platform upon which to build strength, agility and resilience. It’s not a sure thing, though; more than a few ‘white elephant’ cases offer cautionary tales that industrial stakeholders would be wise to reflect upon.

When a country is resource-rich—such as in the case of an oil and gas producer—state-led economic development can similarly be uniquely influential as most hydrocarbon revenues accrue to the state, giving it large spending power and influence over the private economy.

Should a country fall into both the categories described above, ie, have a relatively late-developing industrial economy with a nascent private sector and be resource-rich, the role of state-led industrial policy is particularly influential. This is the case for GCC countries, and their governments have driven industrial diversification since at least the 1970s oil boom.

But of course, the world has changed greatly since then. Opportunities for growth through simple energy-intensive heavy industry are largely exhausted, and global manufacturing has become much more technology-intensive.

Thus, the GCC countries have broadened their sectoral ambitions, including in areas where competitive energy prices do not offer such obvious advantages. Post-pandemic nearshoring, supply chain de-risking, and the shrinking reliance of Western economies upon Chinese exports are additional factors changing the landscape.

Proper implementation

This new landscape presents plenty of opportunity for GCC economies, and properly integrated state-led industrial policy can help them realise the moment's potential.

It has to be done right, though, or the opportunity is likely to be squandered by the liabilities of state-generated inefficiencies, wasted resources, and complacency, among others. History makes this abundantly clear.

So, how can GCC countries get it right? Seven key lessons from history highlight the pitfalls and successes of state-led economic development:

- Establish early openness to competition, especially in international markets. This includes setting and publishing targets for success on international markets and avoiding price controls and reliance on government as the main, long-term customer.

- Build advanced capacity to measure performance using commercially robust KPIs. This means deepening capability for data-gathering and analysis across varied metrics, and avoiding metrics that encourage size rather than efficiency.

- Make industrial policy support conditional on performance. Measure performance, drop laggards, and cut losses when needed, even when this is politically challenging. Use incremental investments across wide-ranging experimentation rather than a few high-stakes bets.

- Set consistent and narrow priorities for industrial policy. Clearly define a hierarchy of objectives, including diversification and profitability; establish minimum commercial targets. Local employment, regional development, and similar non-commercial targets can be incentivised but should not typically constrain industrial policy that aims to discover new products and business models.

- Use high-powered lead agencies. Create or support a small, agile, separate agency to consolidate the institutional landscape, avoid siloed structures, and measure and analyse performance in partnership with universities and research institutes.

- Crowd in the private sector as soon as possible. Encourage involvement with equal incentives offered to public and private entities and adopt competitive neutrality. Explore how to deploy government investment when needed, but develop an exit strategy for privatisation.

- Move up value chains systematically. Review moonshot strategies to ensure required clusters and suppliers are accessible, along with skilled workers. Break initiates down into stages with increasing complexity. Build on existing strengths and nurture relevant supplier networks to diversify sectors and move up value chains. Attract foreign owners of technology and encourage the formation of local private industrial clusters that can serve new sectors.

Getting state-led industrial policy right in a way that will realise potential without oversteer comes down to finding the balance. Call it what you like—the sweet spot, the middle path, or the proverbial golden mean. The waypoints on the roadmap to success include the right mix of support and accountability, meaningful measurement, clear priorities, expert leadership and private sector involvement.

For a deeper look at the ideas presented in this essay, see “Potentials and Pitfalls in Industrial Policy: What Works (and What Doesn’t) in State-led Diversification from Strategy&

You might also like...

Dubai approves designs for $35bn Al Maktoum airport

28 April 2024

TotalEnergies to acquire remaining 50% SapuraOMV stake

26 April 2024

Hyundai E&C breaks ground on Jafurah gas project

26 April 2024

Abu Dhabi signs air taxi deals

26 April 2024

A MEED Subscription...

Subscribe or upgrade your current MEED.com package to support your strategic planning with the MENA region’s best source of business information. Proceed to our online shop below to find out more about the features in each package.